What is schistosomiasis?

Schistosomiasis is a tropical disease caused by a parasitic worm. It’s transmitted through contact with fresh water that has been contaminated with the parasite’s larvae.

- Schistosomiasis (also known as bilharzia) is a tropical disease caused by a group of parasitic worms called blood flukes, or schistosomes.

- It affects around 240 million people worldwide and more than 700 million people live in areas where it’s considered ‘endemic’ (or very common). It is most found in communities without clean water, adequate sanitation, or readily available medical treatment.

- Symptoms can range from very mild to chronic, long-term inflammation.

What is schistosomiasis?

- Schistosomiasis (also known as bilharzia) is a tropical disease affecting around 240 million people worldwide.

- It is caused by parasitic worms called schistosomes. These live in fresh water, such as rivers and lakes, in subtropical and tropical regions of the world.

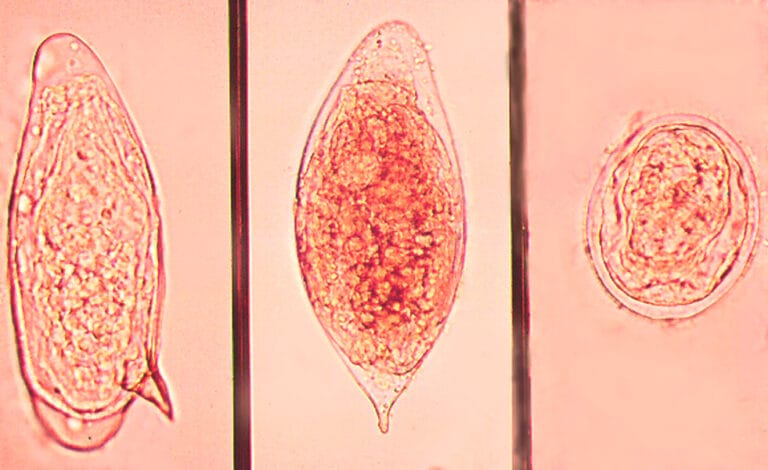

- There are three main species of schistosome that cause schistosomiasis in humans:

- Schistosoma haematobium.

- Schistosoma mansoni.

- Schistosoma japonicum.

- Other species can cause disease in other animals, impacting the animal’s health and the community’s food production.

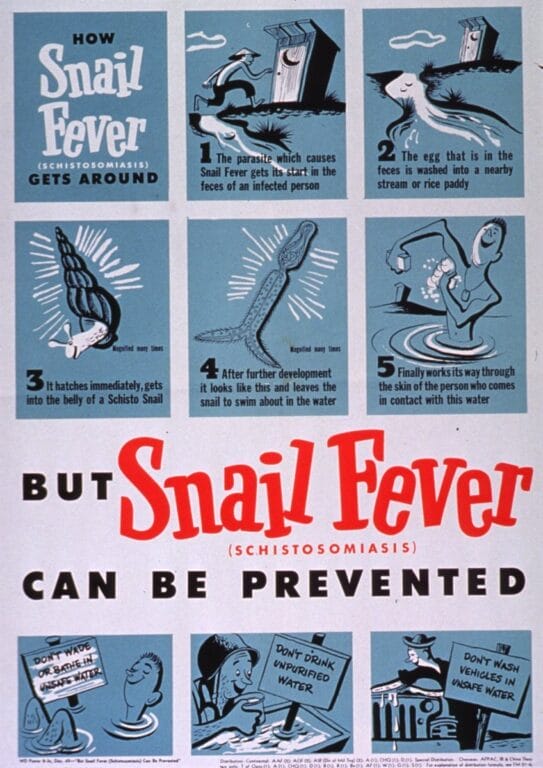

How is schistosomiasis spread?

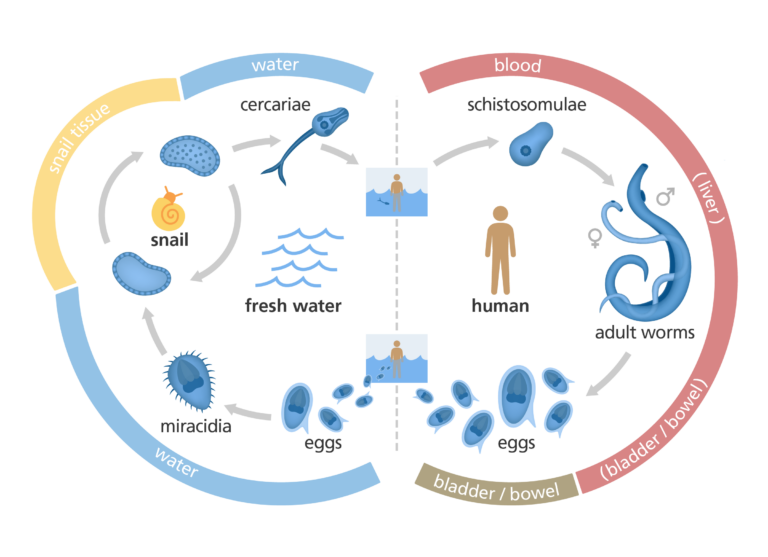

- Schistosomes have a multi-stage life cycle, which you can see in the diagram below. The larval stage lives in freshwater and in snail hosts, while the adult stage lives in humans.

- Fresh water can be contaminated with schistosomes when an infected person urinates or defecates in the water. This releases the parasite’s eggs, which later hatch into larvae.

- Once hatched, the larvae enter different freshwater snails, where they develop and multiply before re-entering the water.

- The parasite can survive for up to 48 hours after it enters the water. During this time, it swims around looking for a human host.

- When the schistosome parasite finds a host in the water, it burrows into their skin.

- Within several weeks the parasite matures and the females produce eggs. Depending on the species of parasite, they migrate to the bowel, rectum or bladder to release the eggs into the urine or faeces and leave the host’s body – and the cycle continues.

- People become infected with schistosomes if they encounter the larval forms in contaminated water, such as when washing or playing. The highest levels of schistosome transmission are in communities living near freshwater lakes and rivers.

- Increasing population sizes is also leading to higher rates of transmission as demand for water increases with more people sharing limited freshwater supplies.

What are the symptoms of schistosomiasis?

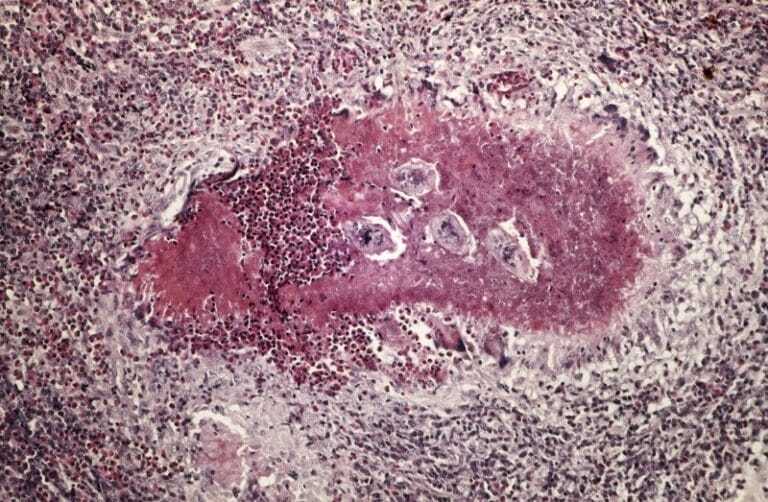

- The symptoms of schistosomiasis are caused by the body’s immune system reacting to the schistosome eggs. Symptoms vary depending on the location of the eggs in the body.

- Schistosome eggs can lodge themselves in many areas in the body, causing inflammation and swelling. This leads to formation of tissue masses called granulomas and stiffening of the tissue called fibrosis.

- Children who are repeatedly infected with schistosomiasis (due to constant exposure to contaminated water) can develop anaemia, malnutrition and learning disabilities.

- The intensity and prevalence of infection and symptoms peaks at around 15-20 years of age. As people get older, although the prevalence of infection tends to stay the same, the number of parasites in the body (parasite burden) has been seen to decrease.

- Schistosomiasis has both an ‘acute’ (shorter term) and ‘chronic’ (longer term) phase.

Acute schistosomiasis

- In acute schistosomiasis, symptoms are caused by the immune system reacting to the parasite and are generally short-term and mild – sometimes so mild they go unnoticed.

- Symptoms develop a few weeks after the parasite first burrows into the individual’s skin.

- Acute symptoms are generally flu-like, including a high temperature and muscle aches, but can also include a skin rash, cough and abdominal pain. This is usually in response to the first parasite eggs getting trapped in the liver and spleen.

Chronic schistosomiasis

- In areas of the world where people don’t have access to medical care and may already have a weak immune system, schistosomiasis can become chronic. This means that schistosomiasis persists for a long time in the body.

- Chronic schistosomiasis can develop months or even years after the initial infection and cause long-term health problems. Damage to the organs after chronic infection is irreversible.

- Symptoms of chronic schistosomiasis result from the inflammation and scarring of various tissues and organs caused by the body’s immune response to the schistosome eggs. This includes:

- Pain when urinating: schistosome eggs lodged in the urinary tract cause inflammation and result in symptoms similar to urinary tract and bladder infections. In rare cases this has been found to predispose individuals to bladder cancer. This can also lead to damage to the cervix, fallopian tubes and vagina.

- Blood in the urine: the result of a severe bladder inflammation caused by eggs lodged in blood vessels in the wall of the bladder.

- Bloody diarrhoea: caused by schistosome eggs lodged in the blood vessels of the intestine and causing inflammation.

- Chest pain: the result of larval parasites moving though the lung tissue and, later, eggs becoming trapped in the blood vessels that supply the lungs.

- Liver failure: caused by the immune response to schistosome eggs lodged in the blood vessels supplying the liver, forming granulomas and scar tissue. These can eventually stop the liver from performing its normal functions leading to a build-up of toxins in the body.

- Seizures (such as a stroke or fit) and paralysis: the result of schistosome eggs lodging in the spinal cord or brain, causing inflammation.

How is schistosomiasis diagnosed?

- Several tests can diagnose a person with schistosomiasis.

- Under a microscope, urine and faeces samples can be studied for the presence of live schistosome eggs. This test is sometimes used to screen whole communities for evidence of schistosome eggs.

- Blood tests can show if an individual has anaemia or if their liver or kidney function has been affected. These may be signs of schistosomiasis.

- A chest X-ray can show if the lungs are damaged by fibrosis and inflammation which may be due to parasite larvae migrating to the lungs or eggs getting trapped in lung tissue.

- An ultrasound scan can show if there is damage to the liver or heart. This damage may be due to schistosome eggs migrating to these organs and causing inflammation.

- A colonoscopy (looking at the bowel with a camera) or cystoscopy (looking at the bladder with a camera) can be used to show if eggs or inflammation are visible in the bladder or bowel.

How is schistosomiasis treated?

- Almost all people who receive treatment for schistosomiasis will get better.

- The primary drug for treating the infection schistosomiasis is called praziquantel. This works by killing the adult worms by causing severe spasms and paralysis in their muscles. Their remains are then broken down naturally by the body.

- Praziquantel can kill the parasites at any time after they become adult worms (usually six weeks after infection), including in patients with chronic infection. However, it is not effective at clearing infection if the parasite is still immature.

- Older drugs are still widely used in the treatment of schistosomiasis. These include metrifonate, which is effective against S haematobium, and oxamniquine, which is effective against S mansoni.

- Mass treatment of entire communities is not considered cost-effective unless there is evidence that at least 75% of the population is infected.

How can schistosomiasis be prevented?

- Schistosomiasis is difficult to avoid in communities with poor sanitation and limited clean water for drinking and bathing.

- The risk of schistosomiasis can be reduced by improving water quality through piped drinking water supplies and more efficient sewage disposal. It can be further reduced by educating communities to avoid swimming in freshwater rivers and lakes.

- Water supplies can also be treated with chemicals to reduce the number of snails, thus removing the ‘intermediate host’ that allows the parasite to develop into cercariae. However, there is a risk that this will harm other species of animal in the water.

- The World Health Organization has a strategy to help control the parasite in high-risk countries. This involves regular treatment of at-risk groups with drugs such as praziquantel, known as preventative chemotherapy.

- There is currently no vaccine available to prevent schistosomiasis.