Unsung heroes in science: Margaret Hamilton

Margaret Hamilton was a computer scientist who spearheaded software engineering whilst working at NASA during the Apollo missions.

Key terms

Bioinformatics

The interdisciplinary field of science which uses computer methods and softwares to understand biological data.

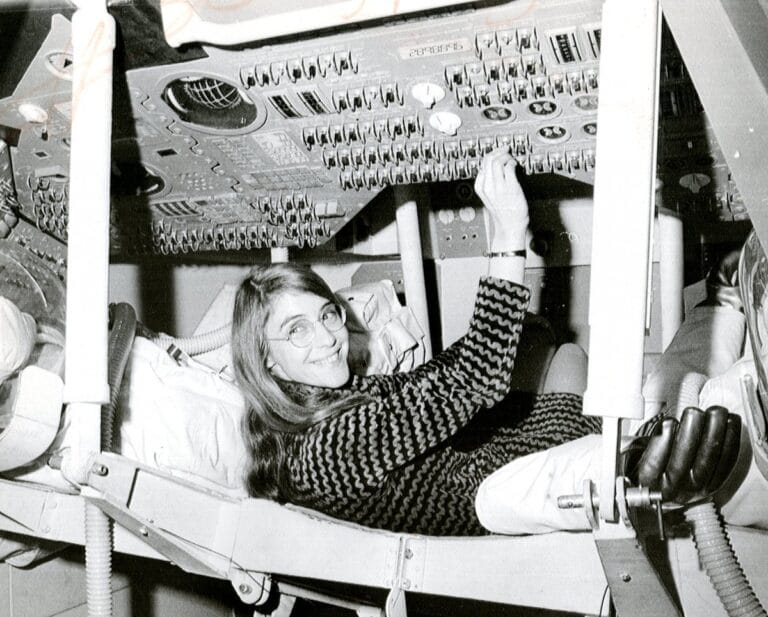

It's 20th July 1969, and the world watches as the Eagle approaches the moon’s surface. Just before landing, a flashing emergency light goes off in the spacecraft. It warns of a hardware issue, and the astronauts must think quickly. Margaret Hamilton watches on from MIT, with a direct feed from Ground Control. With complete confidence in the software that she and her team have created, she informs the crew to continue with their approach. And so, the Eagle has landed.

Early life

Margaret Hamilton was born in Paoli, Indiana on the 17th August 1936. Her family moved to Michigan, which is where she attended high school and started college, before transferring to Earlham College. She graduated in 1958 with a degree in mathematics, with a minor in philosophy. She was newly married with a young daughter, and took a job with a maths lab at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), to support her family. Here she learned about computers, how they worked and how to program them. Computer science was not yet a taught subject - you couldn’t go to university and study computer or software development, you had to learn on the job. It was in this lab that she really developed her love for software engineering.

Hamilton was set to return to graduate school to continue her maths studies, when her husband saw an ad in the paper. The MIT instrumentation laboratory was hiring people to create the software that would “send man to the moon”. This lab would be responsible for designing software for NASA, and the work they did would be used as the onboard flight software for the Apollo project. Hamilton was taken with the idea of a new challenge, and was subsequently hired. There were male engineers already working in the same lab, but they were solely focused on developing the hardware. She was the first software developer to start in the lab, and the first woman they hired.

An important mission

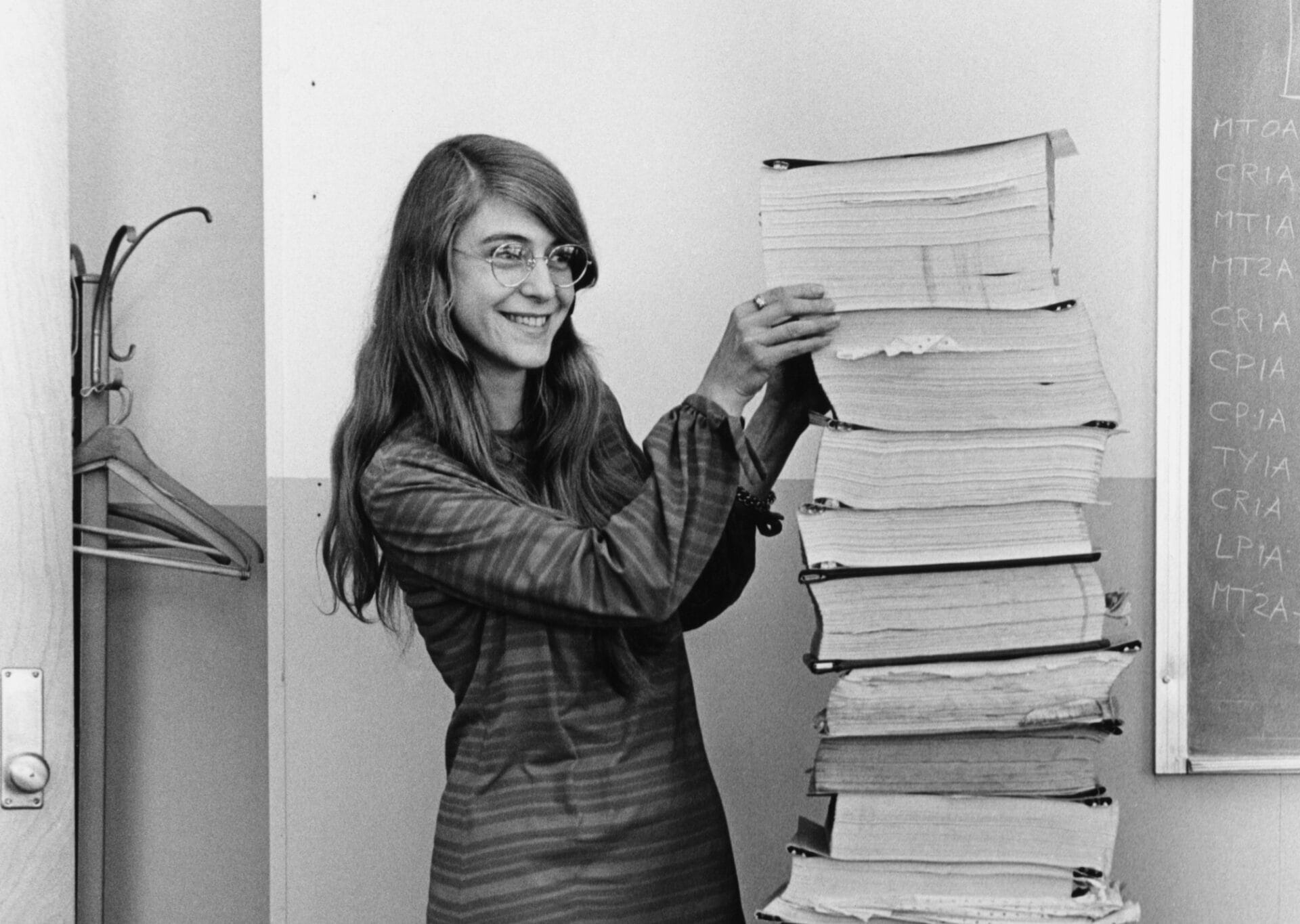

Hamilton began working on the computer programs for the uncrewed Apollo missions, but was soon promoted to head up the group that would develop for the crewed missions, including Apollo 11. At first, no one placed much importance on the software, but they soon began to realise just how crucial it was to the missions. This resulted in the necessary expansion of the team, and soon Hamilton was in charge of a team of 100 software engineers.

Hamilton’s team had to develop incredibly reliable and robust programs, focused on error detection and recovery in case of emergencies; this emergency system kicked in during Apollo 11. It became clear that not only was the software able to warn the astronauts about the fault, but it was actively solving the issues at hand. Hamilton’s software had come to the rescue.

The Lauren bug

Emergency detection was always a priority to Hamilton. Occasionally she would bring her young daughter, Lauren, to the MIT lab. Hamilton recalls a time running a simulation of a moon mission. Lauren began playing with the keys and suddenly, the simulation started. Then she hit a few more keys, and the simulation crashed - Lauren had activated a set of instructions that should be run pre-launch, however she was already en route to the moon in the simulation. Hamilton realised that this could happen during the real mission and that they needed a code for this.

Her superiors believed the astronauts would never make a mistake like this, and therefore it would be a waste of time to plan for it. However, on the very next mission, Apollo 8, the exact scenario happened. She called it ‘the Lauren bug’. Now the higher ups knew better than to dismiss her ideas, and she was asked to program the fix for the bug.

Software supreme

There were very few women involved in writing software at this time. There were a certain number of ‘human computers’ at NASA, and these ‘human computers’ were mostly women. Brilliant, intelligent women who did maths calculation by hand. They were not, however, writing software.

When Hamilton began in this role to develop for the Apollo missions, she was the only woman writing complex computer programs, and she hired a few more for her team, but ultimately it was male-dominated. This is a fact of the software engineering discipline that remains true to this today. Women are certainly outnumbered in the field, but due to the handwork and perseverance of women who code everywhere, this fact is changing.

Over time, it became clear to all those involved in the Apollo missions that software was just as important as the hardware. Hamilton began to refer to the work her team" was doing as engineering, in an attempt to get those around her to take her work more seriously. The work fits the description, it was the design and implementation of complex systems, but was still taken by the hardware experts as a bit of a joke. That was until one day, a senior member of the lab said that he agreed with Hamilton - and thus the term software engineering stuck!

Whilst Hamilton’s work focused on space travel, software engineering is a diverse field that is drawn upon across many STEM disciplines. In biology, bioinformatics software engineers are essential in creating software that aids in the storage, organisation and visualisation of genomics data collected in labs.

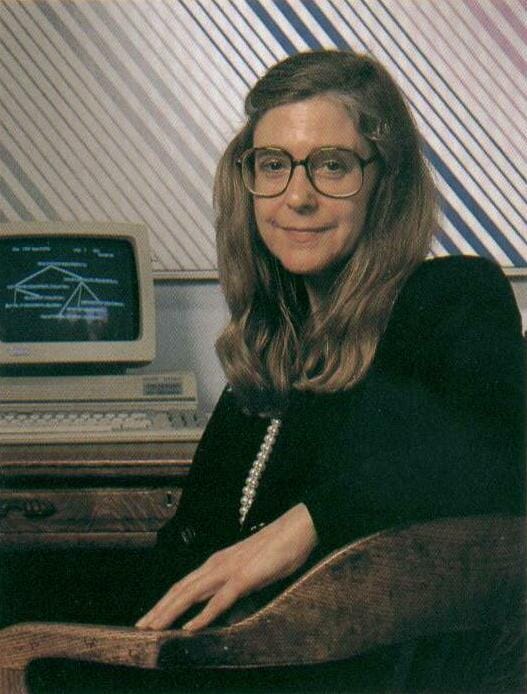

An accomplished scientist

Hamilton continued to excel - her work has been used in the first space stations, as well as in the space shuttle programme. She went on to start her own businesses, and has published more than 130 papers on computer science. She has received the presidential medal of freedom from Barack Obama, as well as numerous other awards and accolades.

She continues to be a role model for women in STEM. In a 2019 interview, she was asked if she had any advice for young women interested in coding: “Don’t let fear get in the way and don’t be afraid to say 'I don’t know' or 'I don’t understand' – no question is a dumb question. And don’t always listen to the so-called experts!”.

Article written by Emma Cooke, Software Developer at EMBL-EBI