How did the Human Genome Project come about?

The Human Genome Project was so big that at the time no one thought it would be possible. But with the support of key scientists and considerable funding, it officially began in 1990.

This part 2 in our series of stories looking at the Human Genome Project. Read part 1 here.

Key terms

Genome

The complete set of genetic instructions required to build and maintain an organism.

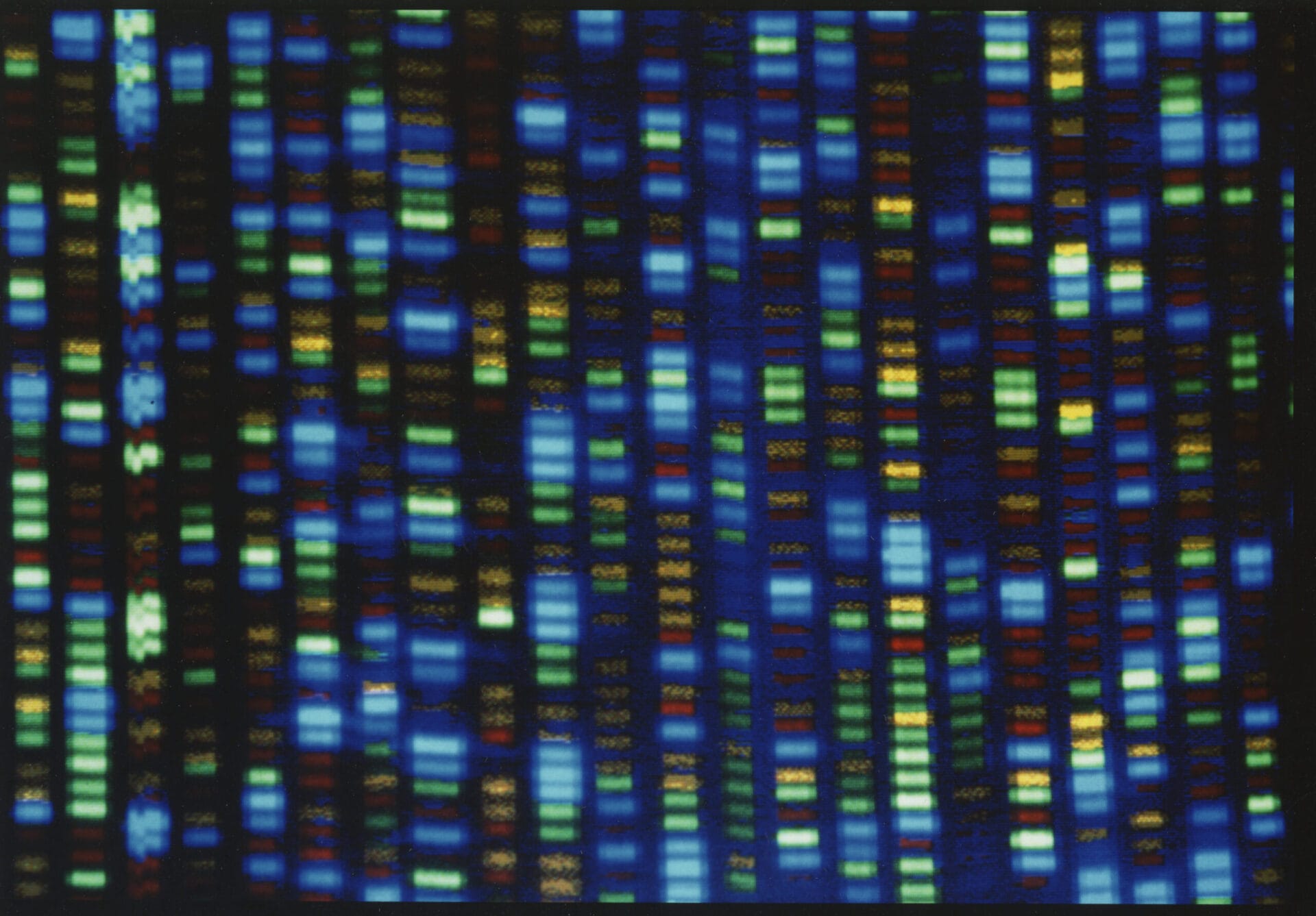

DNA sequencing

The process of determining the order of bases in a section of DNA.

No one had attempted a biology project of such scale before the Human Genome Project.

The development of the first DNA sequencing techniques during the 1970s was a significant catalyst for scientists to start thinking about sequencing the human genome: a Human Genome Project.

At first, the idea of sequencing the entire human genome seemed impossible. This was ‘big science’ – from its huge financial cost to the number of scientists and scale of resources required. No one had ever attempted a biology project on such a huge scale.

Robert Sinsheimer, a molecular biologist and Chancellor of the University of California Santa Cruz, was the first person to take a real chance on the Human Genome Project. Used to raising huge sums of money for physics and astronomy projects, he didn’t see any reason why he couldn’t do the same for a biology project. He was also keen to set up an institute at Santa Cruz, to help put them on the scientific map.

Robert Sinsheimer was the first person to take a real chance on the Human Genome Project.

By the mid-1980s, more and more people supported the idea, deciding that the cost and time needed would be well worth the outcome: a fully sequenced human genome.

Enthusiasm spread to two organisations that would provide considerable amounts of funding – the US Department of Energy and the National Institutes of Health. James Watson, who co-discovered the structure of DNA, also came on board during these discussions, giving the project significant momentum.

The UK took a little longer to convince. Eventually in 1989, with the support of the Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, the Medical Research Council released £11m towards the project for the next three years.

The press had mixed opinions with some describing the project as the “holy grail of biology” – and others predicting it would be a scientific disaster!

Initially, many outside the scientific community were concerned that the Human Genome Project would not be worth this large amount of money and that spending so much on one project was taking funding away from other worthy areas of science. The press also had mixed opinions, with some journalists describing the project as the “holy grail of biology” – and others predicting it would be a scientific disaster!

Despite this, the go-ahead was given, and scientists tried their best to assure the public that it was not just some crazy, unachievable dream. As one doctor John Collee wrote in the Observer in 1992: “The human genome sounds like a mad scientist’s fantasy. So does the Channel Tunnel, but I can assure you that work is in progress on both projects.”

Once given the go-ahead, work moved forward quickly. During the 1990s, Fred Sanger’s sequencing method was automated and used successfully, by John Sulston and Bob Waterston, to sequence the genome of the nematode worm, C. elegans. This work acted as a test project for sequencing the human genome.

It was then up to the Human Genome Project team to follow their lead and sequence the human genome.