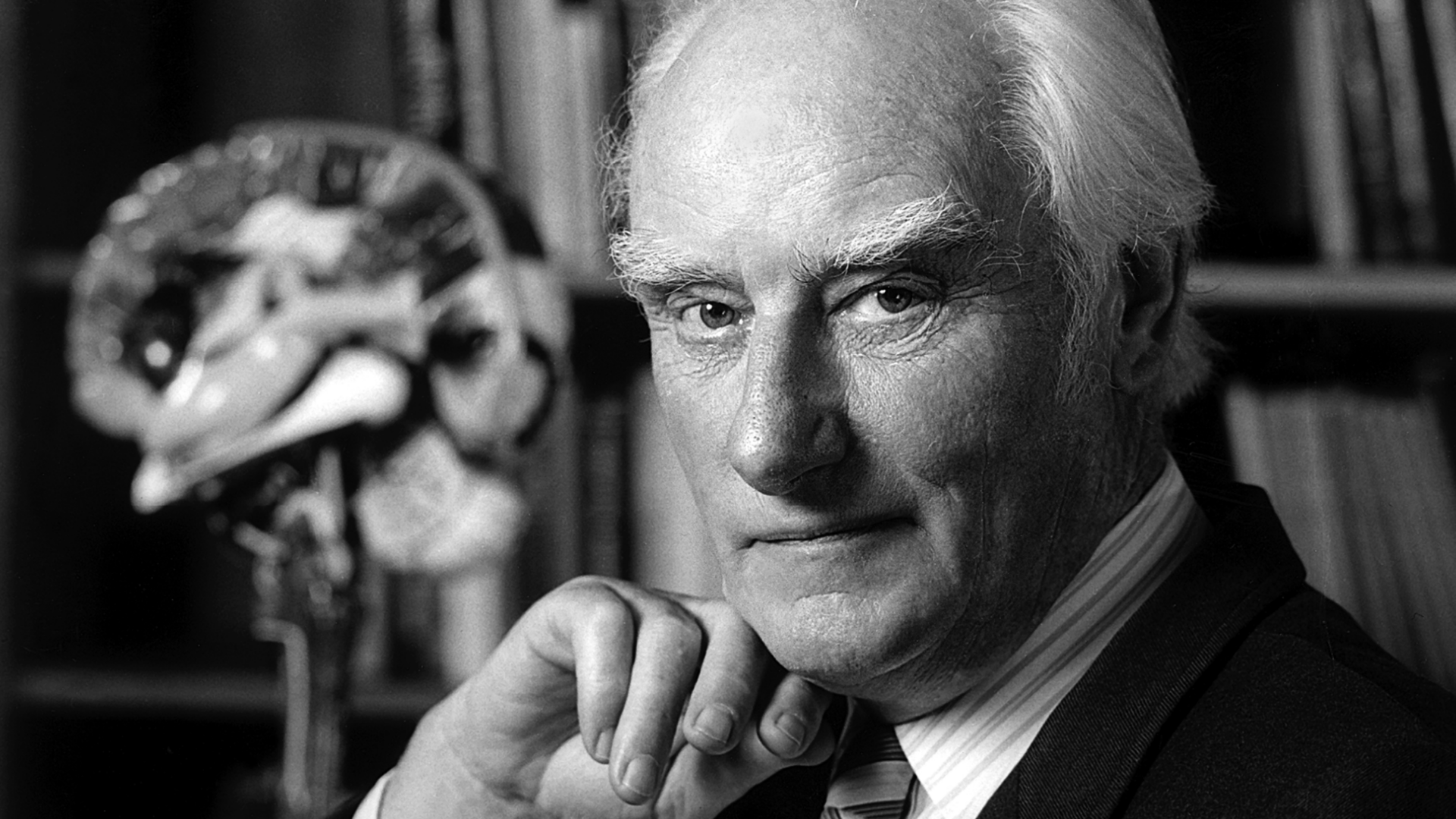

Giants in genomics: Francis Crick

Francis Crick was the co-discoverer of the double helix structure of DNA. For this fundamental finding Francis, James Watson and Maurice Wilkins were awarded the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine in 1962.

Key terms

DNA

(deoxyribonucleic acid) A molecule that carries the genetic information necessary to build and maintain an organism.

RNA

(ribonucleic acid) A single-stranded molecule that acts as an information messenger or occasional information storage.

Early life

Francis Crick was born in Northampton, UK, in 1916. He began his academic career studying physics at University College London, where he graduated in 1937. He was keen to carry on studying towards his PhD straight away, but his plans were put on hold when the Second World War broke out in 1939. Instead, for the next eight years he worked for the British Admiralty developing mines for the Royal Navy.

During this period, Francis came across the book What is Life? by Austrian quantum physicist Erwin Schrödinger. As a result, he decided to change paths from researching physics in London to studying biology in Cambridge, first at the Strangeways Research Laboratory and then later at the Cavendish Laboratory.

A new friendship

When James Watson arrived in Cambridge, the two scientists struck up a strong and very successful friendship – despite Francis being 12 years older than James.

They shared similar scientific interests and were keen to discover the structure of DNA. Francis, fiercely intelligent, worked well in the company of other scientists against whom he could spark ideas, and James insisted on surrounding himself with intelligent people, so the partnership was ideal.

In 1953, after working with numerous models and X-ray images, the pair published their conclusions about the double helix structure of DNA and how it replicates. For this fundamental finding Francis, James and Maurice Wilkins were awarded the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine in 1962.

In 1953, Francis Crick and James Watson published their conclusions about the double helix structure of DNA and how it replicates in Nature magazine.

The role of Rosalind Franklin

To this day there has been much discussion about the role Rosalind Franklin had in the work of Francis Crick and James Watson. It’s known that Francis and James gained a crucial insight from her work that most likely had great advantages for their own progress. However, Rosalind received very little credit in their accounts of what happened.

While Francis and James were carrying out their research to discover the structure of DNA, Rosalind was also using X-ray crystallography in the hope of making the same breakthrough. She and her PhD student, Raymond Gosling, produced an X-ray image of DNA that allowed them to draw conclusions about the double helix shape of DNA. Her data went unpublished but was shown to Francis and James, without her knowledge, by Maurice Wilkins.

Rosalind’s data provided evidence that was fundamental to Francis and James’ discovery – but they barely acknowledged her contribution when it came to publishing the results. Tragically, Rosalind died before she could get any of the recognition she deserved.

Despite Francis and James’ huge breakthrough about the structure of DNA many questions remained as to how the sequence of four bases could instruct the assembly of proteins.

Answering important questions

After publishing their breakthrough findings, Francis remained in the UK and continued to study DNA. In collaboration with Sydney Brenner, he focused on the biochemical processes involved in the construction of proteins and the ways that our genes control this.

Despite Francis and James’ huge breakthrough in discovering the structure of DNA, many questions still remained as to how the sequence of four bases of DNA could instruct the assembly of different amino acids to form proteins. The result of Francis’ research on this was the ‘sequence hypothesis’ where he stated that genetic information was held in the sequence of bases in DNA.

The central dogma

Francis’ discoveries didn’t stop there. In 1958, he and his new research partner, the physicist George Gamow, proposed how DNA directs protein synthesis in a cell. George put forward the first suggestion that explained how the bases in DNA code for amino acids, the building blocks of proteins. Although containing some errors, Francis later stated that George’s ideas were key in inspiring him to consider the problem.

As a result, Francis came up with the ‘central dogma’ of molecular biology. It outlined how DNA codes for proteins by transferring information from DNA to RNA, which is then ‘read’ in groups of three letters, or triplets, to produce a chain of amino acids that makes up a protein. Francis first explained this in 1958 but it wasn’t until 1970 that the theory was reaffirmed and published in Nature magazine.

Image credit: Wikimedia

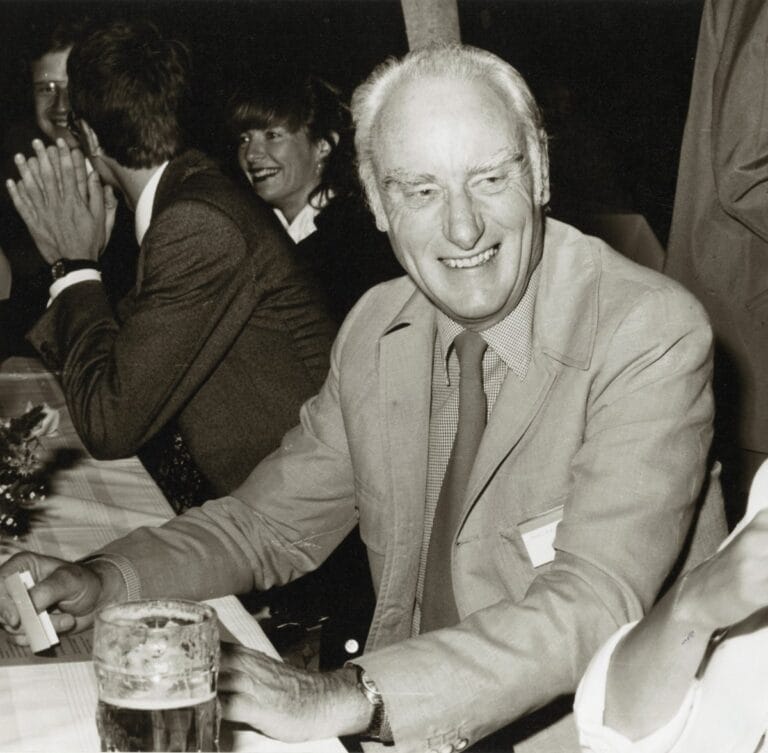

Francis Crick’s accolades

In 1959, Francis was made a Fellow of the Royal Society. He then joined the Salk Institute in California in 1976 where his research changed to focus on the brain and consciousness.

In addition to the Nobel Prize he was awarded in 1962, Francis’ honours included the Lasker Award, the Award of Merit from the Gairdner Foundation, and the Prix Charles Leopold Meyer of the French Academy of Sciences. He was a member of the US National Academy of Sciences, the Royal Society, the French Academy of Sciences and the Irish Academy.

Francis died of colon cancer in 2004, aged 88. A public memorial to celebrate his life and work was held at the Salk Institute with a number of guest speakers, including James Watson and Sydney Brenner.

The Francis Crick Institute opened in 2016, in recognition of his contributions to understanding the genetic code – the key to understanding how living things work.

It’s important to note that Francis Crick occasionally expressed feelings on eugenics, usually in private letters. For example, he advocated a form of positive eugenics in which wealthy parents would be encouraged to have more children.